Android Architecture: Dynamic Parameters in Use Cases.

Your architectural approach should be adaptable enough to fulfill your requirements. In this article we will explore how we can convert our use cases to use dynamic parameters and gain more execution flexibility.

“If you think good architecture is expensive, try bad architecture.”

- Introduction

- Why this article?

- Use cases and dynamic parameters

- Solution 1: the workaround

- Solution 2: the power of refactoring

- Conclusion

- Further Reading

Introduction

Code is about evolution: A lot has been going on since my first approach of Android Architecture more than 2 years ago:

The repo has changed a lot, and people are still contributing and providing a lot of feedback. Kudos to the community!

Why this article?

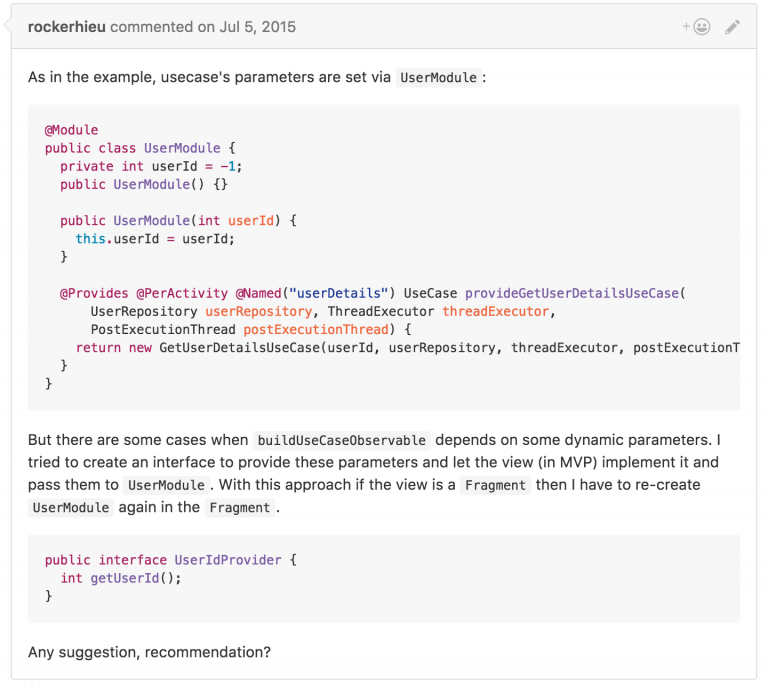

Everything started with a simple question on Github:

I know that it was some time ago, but I think it is worth to expose and share my idea with all of you here. As a plus, I really encourage you to look into all the discussions happening on github, if you have not done it yet. There is a lot of valuable information. Also, in order to better understand this writing, I recommend you to revisit those articles mentioned above.

Use cases and dynamic parameters

In a nutshell and to put you in context, the android architecture example has 2 main use cases:

We are going to focus on “GetUserDetails” here. Why? Because this one needs a dynamic parameter (userId) to return the right data for an specific user and show it on the UI.

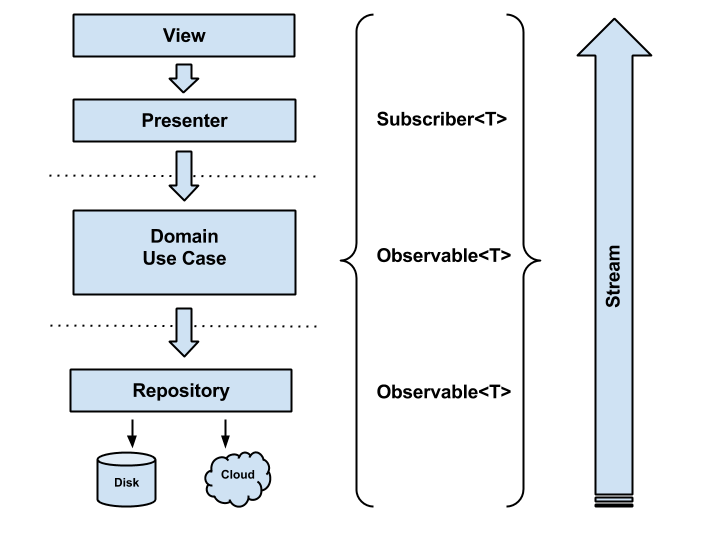

To facilitate understanding this in a easier way, look at the following picture as a reminder of the architecture, where we have presenters which contain “UseCase” classes as collaborators:

This is the original implementation of the already mentioned GetUserDetails.java:

/**

* This class is an implementation of {@link UseCase} that represents a

* use case for retrieving data related to an specific {@link User}.

*/

public class GetUserDetails extends UseCase {

private final int userId;

private final UserRepository userRepository;

@Inject

public GetUserDetails(int userId, UserRepository userRepository,

ThreadExecutor threadExecutor, PostExecutionThread postExecutionThread) {

super(threadExecutor, postExecutionThread);

this.userId = userId;

this.userRepository = userRepository;

}

@Override protected Observable buildUseCaseObservable() {

return this.userRepository.user(this.userId);

}

}

As you can see, this “use case” inherits from a UseCase.java class, which by nature, makes sure that every single “UseCase” runs on a separate thread out of the Android main one, which is a good thing, remember? We want to provide users with a smooth experience and thus, not overload the Android main UI thread.

There is a clear problem with this class design: RIGIDNESS, which means that we are injecting the “userId” parameter in the constructor (at a Dagger module level: UserModule.java which limits us in case we do not know that variable value at the moment of our presenter instantiation.

In fact, this is a valid approach and works for this specific case but, what happens if we have a “LoginUserUseCase” for example? We suffer from the lack of that flexibility because we do not know upfront “username” and “password” when we instantiate our potential LoginPresenter.java class.

We need to find a simple way to pass in parameters when building the observable (through the abstract method buildUseCaseObservable()) which is responsible for emitting the items needed for our use case execution.

This is the original method signature:

/**

* Builds an {@link Observable} which will be used when executing

* the current {@link UseCase}.

*/

protected abstract Observable buildUseCaseObservable();

Solution 1: the workaround

We can use Optional<T> to pass in parameters and change the signature of the method to look like as following:

/**

* Builds an {@link Observable} which will be used when executing

* the current {@link UseCase}.

*/

protected abstract Observable buildUseCaseObservable(Optional<Params> params);

I consider this a VALID solution by using Optional<T> for optional parameters, that may be required or not for certain UseCase classes.

By the way, I’m not going to talk about the benefits of using Optional<T> on Android since I have already done it in the past.

GetUserDetails.java class implementation

This is now the final result of our modified GetUserDetails.java class:

/**

* This class is an implementation of {@link UseCase} that represents a use case for

* retrieving data related to an specific {@link User}.

*/

public class GetUserDetails extends UseCase {

public static final String NAME = "userDetails";

public static final String PARAM_USER_ID_KEY = "userId";

@VisibleForTesting

static final int PARAM_USER_ID_DEFAULT_VALUE = -1;

private final UserRepository userRepository;

@Inject

public GetUserDetails(UserRepository userRepository, ThreadExecutor threadExecutor,

PostExecutionThread postExecutionThread) {

super(threadExecutor, postExecutionThread);

this.userRepository = userRepository;

}

@Override protected Observable buildUseCaseObservable(Optional<Params> params) {

if (params.isPresent()) {

final int userId = params.get().getInt(PARAM_USER_ID_KEY, PARAM_USER_ID_DEFAULT_VALUE);

return this.userRepository.user(userId);

} else {

return Observable.empty();

}

}

}

We got rid of our dynamic parameter in the constructor and we pass it in when we execute the UseCase. And by using Optional<Param> we make sure that any client (UseCase) wanting to unwrap “Params” will have to check their availability first. Here is the commit with all the modifications to the repo if you want to dive deeper.

Params.java class implementation

This is no more than a class backed by a Map<T, K> which stores the parameters.

Basically I followed up the principles of the well known Bundle.java class on Android, but since I did not want to have any dependencies on the framework at a domain layer level, I opted for my own implementation.

You may argue that this is reinventing the wheel but from my perspective, it is a very simple class (wrapper) with a clear purpose.

By the way, this is how it looks like:

/**

* Class backed by a Map, used to pass parameters to {@link UseCase} instances.

*/

public final class Params {

public static final Params EMPTY = Params.create();

private final Map<String, Object> parameters = new HashMap<>();

private Params() {}

public static Params create() {

return new Params();

}

public void putInt(String key, int value) {

parameters.put(key, value);

}

int getInt(String key, int defaultValue) {

final Object object = parameters.get(key);

if (object == null) {

return defaultValue;

}

try {

return (int) object;

} catch (ClassCastException e) {

return defaultValue;

}

}

}

You can grow this class or refactor it depending on your requirements/needs.

Solution 2: the power of refactoring

After discussing with the community I came up with a more elegant solution.

It is worth mentioning that I wanted to keep the original one in this article to actually show how we can evolve our code by receiving constructive feedback and seeing how other professionals solve the same problems: The magic of refactoring.

This second approach consists of making our UseCase java class generic, which now requires 2 parameterized types:

T: The use case **Observable** return type Param: A class type (inner in my implementation) which is specific to each use case, that will wrap all the execution environment values required in order to execute our use case.

UseCase.java class implementation

public abstract class UseCase<T, Params> {

...

/**

* Builds an {@link Observable} which will be used when executing

* the current {@link UseCase}.

*/

abstract Observable<T> buildUseCaseObservable(Params params);

/**

* Executes the current use case.

*

* @param observer {@link DisposableObserver} which will be listening to the

* observable build by {@link #buildUseCaseObservable(Params)} ()} method.

* @param params Parameters (Optional) used to build/execute this use case.

*/

public void execute(DisposableObserver<T> observer, Params params) {

Preconditions.checkNotNull(observer);

final Observable<T> observable = this.buildUseCaseObservable(params)

.subscribeOn(Schedulers.from(threadExecutor))

.observeOn(postExecutionThread.getScheduler());

addDisposable(observable.subscribeWith(observer));

}

...

}

The main benefit of this is that you get better semantics because our inner “param” class can contain its properly named fields, getters and setters.

GetUserDetails.java class implementation

/**

* This class is an implementation of {@link UseCase} that represents a use case for

* retrieving data related to an specific {@link User}.

*/

public class GetUserDetails extends UseCase<User, GetUserDetails.Params> {

private final UserRepository userRepository;

@Inject

GetUserDetails(UserRepository userRepository, ThreadExecutor threadExecutor,

PostExecutionThread postExecutionThread) {

super(threadExecutor, postExecutionThread);

this.userRepository = userRepository;

}

@Override Observable<User> buildUseCaseObservable(Params params) {

Preconditions.checkNotNull(params);

return this.userRepository.user(params.userId);

}

public static final class Params {

private final int userId;

private Params(int userId) {

this.userId = userId;

}

public static Params forUser(int userId) {

return new Params(userId);

}

}

}

GetUserList.java class implementation

There is another question that comes to my mind: What happens with a UseCase with empty parameters? We can just use “Void” as “Param” type. For example, our “GetUserList” use case which does not require any extra data to be executed:

/**

* This class is an implementation of {@link UseCase} that represents a use case for

* retrieving a collection of all {@link User}.

*/

public class GetUserList extends UseCase<List<User>, Void>; {

private final UserRepository userRepository;

@Inject

GetUserList(UserRepository userRepository, ThreadExecutor threadExecutor,

PostExecutionThread postExecutionThread) {

super(threadExecutor, postExecutionThread);

this.userRepository = userRepository;

}

@Override Observable<List<User>> buildUseCaseObservable(Void unused) {

return this.userRepository.users();

}

}

Again, here is the commit if you want to see all the changes involved.

Conclusion

Here you have 2 simple approaches to use dynamic parameters in Android clean architecture use cases.

Remember that there are NO SILVER BULLETS and you can agree or not with it, but the most important thing is to use WHAT WORKS FOR YOU BASED ON YOUR REQUIREMENTS (Respect software engineering good practices and principles).

Also some advice:

- You establish the RULES for your framework.

- Do not overthink too much.

- Do not put a lot of overhead, start simple and move towards complexity.

- Be open to get constructive feedback.

My original implementation worked but it turned out to not be as FLEXIBLE as I wanted to: the more requirements we have the more we need to evolve our code base. Writing this article was a pending debt to me, but as I love to say: “better late than never”.

Please leave any feedback in the discussions section on Github.