Aspect Oriented Programming in Android.

AOP (Aspect Oriented Programming) is a paradigm that has been with us for many years, and I found it very useful to apply it to Android. After some investigation, I consider that we can get a lot of advantages and very useful stuff when making use of it. Let’s get started!

“Good programmers write code for humans first and computers next.”

- Introduction

- Terminology (Mini glossary)

- So…where and when can we apply AOP?

- Tools and Libraries

- Why AspectJ?

- Example

- Project Structure

- Creating our Annotation

- Our StopWatch for performance monitoring

- DebugLog Class

- Our Aspect

- Making AspectJ to work with Android

- Our test method

- Executing our application

- Recap

- Conclusion

- Source Code

- Resources

Introduction

Aspect-oriented programming entails breaking down program logic into “concerns” (cohesive areas of functionality). This means, that with AOP, we can add executable blocks to some source code without explicitly changing it. This programming paradigm pretends that “cross-cutting concerns” (the logic needed at many places, without a single class where to implement them) should be implemented once and injected it many times into those places.

Code injection becomes a very important part of AOP: it is useful for dealing with the mentioned “concerns” that cut across the whole application, such as logging or performance monitoring, and, using it in this way, should not be something used rarely as you might think, quite the contrary; every programmer will come into a situation where this ability of injecting code, could prevent a lot of pain and frustration.

AOP is a paradigm that has been with us for many years, and I found it very useful to apply it to Android.

After some investigation I consider that we can get a lot of advantages and very useful stuff when making use of it.

Terminology (Mini glossary)

Before we get started, let’s have a look at some vocabulary that we should keep in mind:

Cross-cutting concerns: Even though most classes in an OO model will perform a single, specific function, they often share common, secondary requirements with other classes. For example, we may want to add logging to classes within the data-access layer and also to classes in the UI layer whenever a thread enters or exits a method. Even though each class has a very different primary functionality, the code needed to perform the secondary functionality is often identical.

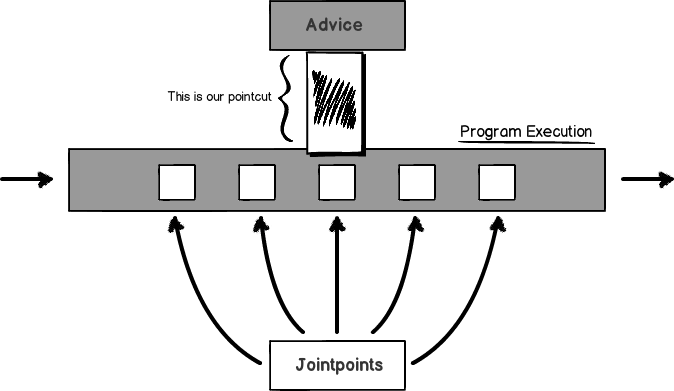

Advice: The code that is injected to a class file. Typically we talk about before, after, and around advices, which are executed before, after, or instead of a target method. It’s possible to make also other changes than injecting code into methods, e.g. adding fields or interfaces to a class.

Joint point: A particular point in a program that might be the target of code injection, e.g. a method call or method entry.

Pointcut: An expression which tells a code injection tool where to inject a particular piece of code, i.e. to which joint points to apply a particular advice. It could select only a single such point – e.g. execution of a single method – or many similar points – e.g. executions of all methods marked with a custom annotation such as @DebugTrace.

Aspect: The combination of the pointcut and the advice is termed an aspect. For instance, we add a logging aspect to our application by defining a pointcut and giving the correct advice.

Weaving: The process of injecting code – advices – into the target places – joint points.

This picture summarizes a bit a few of these concepts:

So…where and when can we apply AOP?

Some examples of cross-cutting concerns are:

- Logging.

- Persistance.

- Performance monitoring.

- Data Validation.

- Caching.

- Many others.

And in relation with “when the magic happens”, the code can be injected at different points in time:

- At run-time: your code has to explicitly ask for the enhanced code, e.g. by using a Dynamic Proxy (this is arguably not true code injection). Anyway here is an example I created for testing it.

- At load-time: the modification are performed when the target classes are being loaded by Dalvik or ART. Byte-code or Dex-code weaving.

- At build-time: you add an extra step to your build process to modify the compiled classes before packaging and deploying your application. Source-code weaving.

Depending on the situation you will be choosing one or the other :).

Tools and Libraries

There are a few tools and libraries out there that help us use AOP:

- AspectJ: A seamless aspect-oriented extension to the Javatm programming language (works with Android).

- Javassist for Android: An android porting of the very well known java library Javassist for bytecode manipulation.

- DexMaker: A Java-language API for doing compile time or runtime code generation targeting the Dalvik VM.

- ASMDEX: A bytecode manipulation library as ASM but it handles the DEX bytecode used by Android executables.

Why AspectJ?

For our example below I have chosen AspectJ for the following reasons:

- Very powerful.

- Supports build time and load time code injection.

- Easy to use.

Example

Let’s say we want to measure the performance of a method (how long takes its execution).

For doing this we want to mark our method with a @DebugTrace annotation and want to see the results using the logcat transparently without having to write code in each annotated method.

Our approach is to use AspectJ for this purpose.

This is what is gonna happen under the hood:

- The annotation will be processed in a new step that we are adding to our compilation fase.

- Necessary boilerplate code will be generated and injected in the annotated method.

I have to say here that while I was researching I found Jake Wharton’s Hugo Library that it is suppose to do the same, so I refactored my code and looks similar to it, although mine is a more primitive and simpler version (I have learnt a lot by looking at its code by the way).

Project Structure

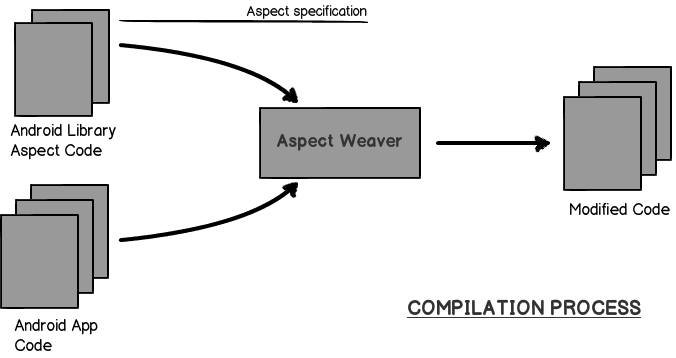

We will break up our sample application into 2 modules, the first will contain our android app and the second will be an android library that will make use of AspectJ library for weaving (code injection).

You may be wondering why we are using an android library module instead of a pure java library: the reason is that for AspectJ to work on Android we have to make use of some hooks when compiling our app and this is only possible using the android-library gradle plugin.

Do not worry about this yet, cause I will be giving some more details later.

Creating our Annotation

We first create our Java annotation, which will be persisted in the class (RetentionPolicy.CLASS) file and we will be able to annotate any constructor or method with it (ElementType.CONSTRUCTOR and ElementType.METHOD).

Our DebugTrace.java file will look like this:

@Retention(RetentionPolicy.CLASS)

@Target({ ElementType.CONSTRUCTOR, ElementType.METHOD })

public @interface DebugTrace {}

Our StopWatch for performance monitoring

I have created a simple class that encapsulates time start/stop.

Here is our StopWatch.java class:

/**

* Class representing a StopWatch for measuring time.

*/

public class StopWatch {

private long startTime;

private long endTime;

private long elapsedTime;

public StopWatch() {

//empty

}

private void reset() {

startTime = 0;

endTime = 0;

elapsedTime = 0;

}

public void start() {

reset();

startTime = System.nanoTime();

}

public void stop() {

if (startTime != 0) {

endTime = System.nanoTime();

elapsedTime = endTime - startTime;

} else {

reset();

}

}

public long getTotalTimeMillis() {

return (elapsedTime != 0) ? TimeUnit.NANOSECONDS.toMillis(endTime - startTime) : 0;

}

}

DebugLog Class

I just decorated the android.util.Log cause my first idea was to add some more functionality to the android log.

Here it is:

/**

* Wrapper around {@link android.util.Log}

*/

public class DebugLog {

private DebugLog() {}

/**

* Send a debug log message

*

* @param tag Source of a log message.

* @param message The message you would like logged.

*/

public static void log(String tag, String message) {

Log.d(tag, message);

}

}

Our Aspect

Now it is time to create our aspect class (TraceAspect.java) that will be in charge of managing the annotation processing and source-code weaving.

/**

* Aspect representing the cross cutting-concern: Method and Constructor Tracing.

*/

@Aspect

public class TraceAspect {

private static final String POINTCUT_METHOD =

"execution(@org.android10.gintonic.annotation.DebugTrace * *(..))";

private static final String POINTCUT_CONSTRUCTOR =

"execution(@org.android10.gintonic.annotation.DebugTrace *.new(..))";

@Pointcut(POINTCUT_METHOD)

public void methodAnnotatedWithDebugTrace() {}

@Pointcut(POINTCUT_CONSTRUCTOR)

public void constructorAnnotatedDebugTrace() {}

@Around("methodAnnotatedWithDebugTrace() || constructorAnnotatedDebugTrace()")

public Object weaveJoinPoint(ProceedingJoinPoint joinPoint) throws Throwable {

MethodSignature methodSignature = (MethodSignature) joinPoint.getSignature();

String className = methodSignature.getDeclaringType().getSimpleName();

String methodName = methodSignature.getName();

final StopWatch stopWatch = new StopWatch();

stopWatch.start();

Object result = joinPoint.proceed();

stopWatch.stop();

DebugLog.log(className, buildLogMessage(methodName, stopWatch.getTotalTimeMillis()));

return result;

}

/**

* Create a log message.

*

* @param methodName A string with the method name.

* @param methodDuration Duration of the method in milliseconds.

* @return A string representing message.

*/

private static String buildLogMessage(String methodName, long methodDuration) {

StringBuilder message = new StringBuilder();

message.append("Gintonic --> ");

message.append(methodName);

message.append(" --> ");

message.append("[");

message.append(methodDuration);

message.append("ms");

message.append("]");

return message.toString();

}

}

Some important points to mention here:

We declare 2 public methods with 2 pointcuts that will filter all methods and constructors annotated with

org.android10.gintonic.annotation.DebugTrace.We define the

weaveJointPoint(ProceedingJoinPoint joinPoint)annotated with@Aroundwhich means that our code injection will happen around the annotated method with@DebugTrace.The line

Object result = joinPoint.proceed();is where the annotated method execution happens, so before this, is where we start our StopWatch to start measuring time, and after that, we stop it.Finally we build our message and print it using the Android Log.

Making AspectJ to work with Android

Now everything should be working, but, if we compile our sample, we will see that nothing happens.

The reason is that we have to use the AspectJ compiler (ajc, an extension of the java compiler) to weave all classes that are affected by an aspect.

That’s why, as I mention before, we need to add some extra configuration to our gradle build task to make it work.

This is how our build.gradle looks like:

import com.android.build.gradle.LibraryPlugin

import org.aspectj.bridge.IMessage

import org.aspectj.bridge.MessageHandler

import org.aspectj.tools.ajc.Main

buildscript {

repositories {

mavenCentral()

}

dependencies {

classpath 'com.android.tools.build:gradle:0.12.+'

classpath 'org.aspectj:aspectjtools:1.8.1'

}

}

apply plugin: 'android-library'

repositories {

mavenCentral()

}

dependencies {

compile 'org.aspectj:aspectjrt:1.8.1'

}

android {

compileSdkVersion 19

buildToolsVersion '19.1.0'

lintOptions {

abortOnError false

}

}

android.libraryVariants.all { variant ->

LibraryPlugin plugin = project.plugins.getPlugin(LibraryPlugin)

JavaCompile javaCompile = variant.javaCompile

javaCompile.doLast {

String[] args = ["-showWeaveInfo",

"-1.5",

"-inpath", javaCompile.destinationDir.toString(),

"-aspectpath", javaCompile.classpath.asPath,

"-d", javaCompile.destinationDir.toString(),

"-classpath", javaCompile.classpath.asPath,

"-bootclasspath", plugin.project.android.bootClasspath.join(

File.pathSeparator)]

MessageHandler handler = new MessageHandler(true);

new Main().run(args, handler)

def log = project.logger

for (IMessage message : handler.getMessages(null, true)) {

switch (message.getKind()) {

case IMessage.ABORT:

case IMessage.ERROR:

case IMessage.FAIL:

log.error message.message, message.thrown

break;

case IMessage.WARNING:

case IMessage.INFO:

log.info message.message, message.thrown

break;

case IMessage.DEBUG:

log.debug message.message, message.thrown

break;

}

}

}

}

Our test method

Let’s use our cool aspect annotation by adding it to a test method.

I have created a method inside the main activity for testing purpose:

@DebugTrace

private void testAnnotatedMethod() {

try {

Thread.sleep(10);

} catch (InterruptedException e) {

e.printStackTrace();

}

}

Executing our application

We build and install our app on an android device/emulator by executing the gradle command:

gradlew clean build installDebug

If we open the logcat and execute our sample, we will see a debug log with:

Gintonic --> testAnnotatedMethod --> [10ms]

Our first android application using AOP worked!

You can use the Dex Dump android application (from your phone), or any any other reverse engineering tool for decompiling the apk and see the source code generated and injected.

Recap

So to recap and summarize:

- We have had a taste of Aspect Oriented programming paradigm.

- Code Injection becomes a very important part of this approach (AOP).

- AspectJ is a very powerful and easy to use tool for source code weaving in Android applications.

- We have created a working example using AOP capabilities.

Conclusion

Aspect Oriented Programming is very powerful. Using it the right way, you can avoid duplicating a lot of code when you have “cross-cutting concerns” in your Android apps, like performance monitoring, as we have seen in our example.

I do encourage you to give it a try, you will find it very useful.

I hope you like the article, the purpose of it was to share what I’ve learnt so far, so feel free to provide feedback, or even better, fork the code and play a bit with it. I’m sure we can add very interesting stuff to our AOP module in the sample app. Ideas are very welcome ;).

Source Code

You can check 2 examples here, the first one uses AspectJ and the second one uses a Dynamic Proxy approach: